I have known Jim Wolcott and his art for more than twenty years, but I admit I was not prepared for his new work—largescale, complex paintings he has been making full time since retiring from medicine.

Jim’s early pieces are probably the only art I have encountered in my life in which surgical gauze plays a starring role. This is not surprising when Jim’s medical career is taken into account. We were in an art show together at my law firm in the 1990s which cast a spotlight on people whose “alter ego” was as an artist. Jim, at the time, was a local radiologist. Jim’s submissions contained framed, careful compositions of gauzes of pale, dyed-colors interlaced with silvery-white birch bark and thin thread and mesh. There was a color field sort of effect, like the monumental canvases of Jules Olitski with their subtle gradations of color, but on a reduced scale. The works floated between the frame glass and a bed of cotton. In later years, cheese cloth then burlap became materials of choice, with gridlines and opacity that lent itself to experiments in layering, composition, and color.

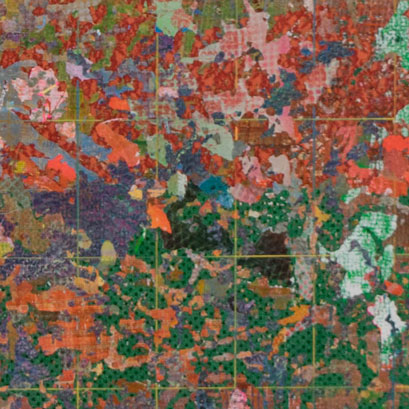

Jim’s new work these decades later is tighter and more forceful. The mixed-media paintings are also approaching a far more monumental scale with some including dimensions approaching eight feet or more. The ephemeral gauze works which seemed constructed half of air have given way to a meticulous and rigorous surface in which unorthodox materials (often purchased at Home Depot) are painstakingly cut and reassembled in large-scale kaleidoscopic surfaces; often with layers of paint or clear gloss applied over them. There is a sensory chaos often both over and under-laid on a grid form. The works remind me of the push and pull between rounded forms and square ones - which marked Piet Mondrian’s transition from painting trees and windmills that ultimately reduced to absolute vertical and horizontal lines in his iconic abstractions. Jim keeps the crackling tension alive between these competing visual agendas of strong lines and turbulent, organic forms.

Left: A detail of one of Jim’s densely multi-layered works which are loosely held together by grids.

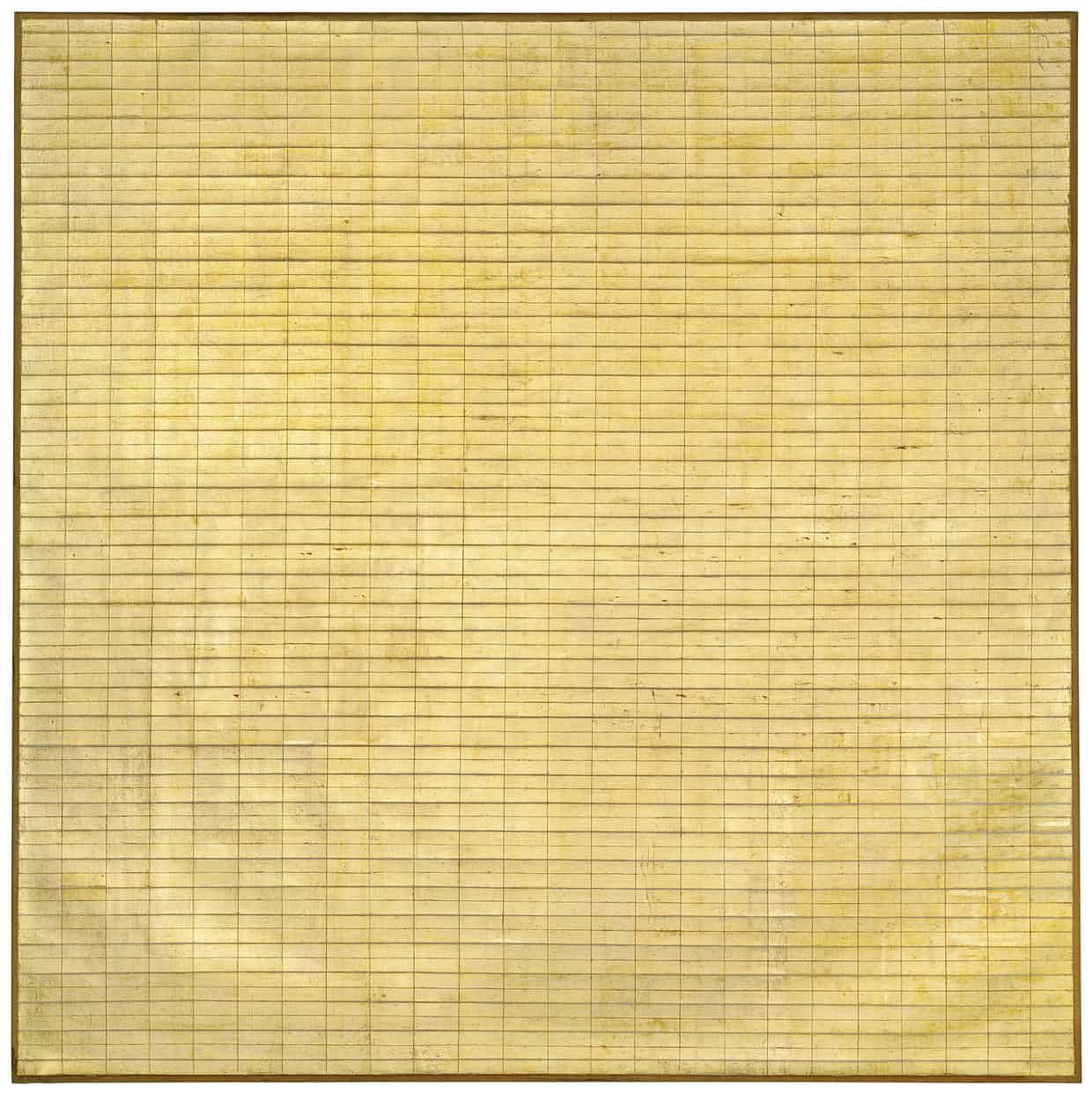

Right: an iconic Agnes Martin grid painting, Friendship, 1963, in which the grid is the principal structure.

When I visited Jim’s studio, the references pinned to a bulletin board of source material confirmed this tension between the elegance of gridlines and organic forms. There is an Agnes Martin photograph. Gustave Klimt and his colorfully-controlled chaos also features. Most moving, is a photo from a New York Times review of an Italian staging of Giacomo Puccini’s Madama Butterfly with riotous pink cherry blossoms set-off against the grid work of Japanese screens and dividers. The transparency of the screens with their grids and organic forms seemingly layered in light has affinity for what Jim endeavors to make in the space between hardline and the organic in his pieces.

A newspaper photo that Jim keeps in his studio. Brescia/Amisano for Teatro alla Scala, from the New York Times.

Candidly, I struggled for some months to jot down my personal reactions to these pieces. Their complexity and shifting images with both bold, repeating patterns and patches of unbound chaos make me think of the interior of the human body. I wondered in what ways a radiologist-turned-artist might be influenced by his prior life peering for hours at end at the vaguest of films in which both the chaos and order of anatomy and disease are infinitely rich visually. As an attorney who has defended cases where a radiologist is alleged to have missed something in those shadowy mirages, I have seen first-hand the subtleties of color and line and shape that are the images which can mean life or death. What is it about such a seeing that may be at work in these explorations? The layering and obscuring are deeply intricate, yet like the body, there is a coherence and a logic tugging at the edges of the whole.

The intricacy of pattern and color-schemes—lots of red and sinew—made me think of a 1960’s Sci Fi film called Fantastic Voyage in which cold warriors and their submarine are shrunk and injected into a human body to perform an emergency surgery from within. The fantastic set-pieces of drooping and undulating and branched vessels and delicately thin tissues is visually stunning. There is something to that visually complex and stimulating imagery that I see in these works.

Stills from the 1966 film, the Fantastic Voyage; note the skeins of intricate body tissue

We might scrape at the surface of the body’s secrets with our MRI’s and CT scans, just as Jim’s new works seem to reach for a truth, the entirety of which is not always in view or even able to be glimpsed in the frame. Yet there is a coherence in the chaos implicit in these pieces that says: “trust your eyes and trust your instincts.” I enjoy these nuanced pieces where exuberance and control are brought together so productively.

Jay Surdukowski

Director, Robert M. Larsen Gallery at Sulloway & Hollis

September 27, 2017